BY AARON SAGERS

(Originally published on TravelChannel.com)

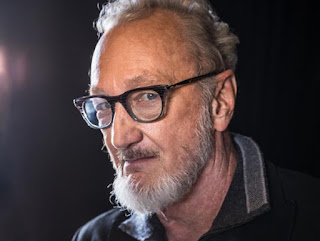

Robert Englund knows something about terror. For nearly 36 years the actor has been best known as the maker of nightmare fuel in the form of dreamscape stalker Freddy Krueger from the A Nightmare on Elm Street franchise. But beyond the role of Freddy, or The Mangler, or The Phantom of the Opera, Englund is a horror icon. His name alone has become synonymous with scary stories.

And in the new series, True Terror with Robert Englund, which airs Wednesdays at 10|9c, his role is that of horror host, sharing stories that are perhaps the scariest because they are ripped from the historical headlines of America’s newspapers. Brought to life via both Englund’s narration and reenactments, these True Terror tales of premonition, monster sightings, premature burials — and yes, even haunted nightmares — are so striking because they are rooted in fact.

In our following conversation, Robert Englund shares his fascination with these stories of the odd, and macabre, and even recounts two tales of the unexplained from his own personal history.

It doesn’t seem like a coincidence that the first story of the first episode involves a man haunted by nightmares of his death. How did you determine the balance between playing up “the man behind Freddy,” and the weird historical tales?

Robert Englund: I obviously bring a lot of baggage to my hosting, and that's one of the reasons they chose me. But one of the producers was particularly obsessed as a young man with Unsolved Mysteries with Robert Stack, and it was his dream to bring something in that spirit to Travel Channel but darker, and much more historical. And I'm a little bit Vincent Price, I'm a little bit Robert Englund, and in some of the writing there's a little bit Rod Serling. But that's that kind of flavor.

Speaking of Serling, your hosting style possesses his similar wry humor, and mischief, but also a trustworthiness as a storyteller.

Englund: Well, thank you. I discovered that in the writing. Some of the tags, some of the recaps, and some of the wind-ups have that Serling rhythm to them. And there's a bit of a wink sometimes. I think there needs to be a bit of a wink, but there also needs to be a bit of a “what if.” What if this happened? Or what could it mean? I like to put that in.

I began as a print journalist working for newspapers, and would discover these archived stories, such as a ghostly postman that kept to his route, reported in serious publications. Do you think these True Terror tales have truth behind them, or they are just the stuff of entertainment during an era of yellow journalism?

Englund: I think it's a combination of tabloid journalism, and human interest stories. The other part is we don't know the morality at the time. People were more open to superstition a hundred years ago, 150 years ago. People were more open to a different kind of conspiracy theory. We were less wise, we were less educated, we knew less science. Things were unexplained, so we believed other things … To understand that morality is to understand why so many of these stories that kind of expose the tabloid dark underbelly of the American psyche, why so many of them were printed in newspapers and why so many of them were believed.

But when you have a story such as a flying dinosaur terrorizing cowboys, what do you think the origins of that sort of tale may be?

Englund: Even as far fetched as our flying dinosaur segment is, imagine if you were in 1840s Arizona or the Southwest somewhere, and you're out by the campfire. You've got a little bit of whiskey in your coffee, and it's evening, and you're leaning up against a warm rock because nighttime is coming, and there's a monitor lizard. Maybe it's a big flying lizard, and you look up and see that thing. The shadow crosses over you, you're a little bit drunk, and it looks like a flying dinosaur. You go into Tombstone the next day, or to Vera Cruz, or to Laredo, and you go into the saloon and talk about what you saw. That becomes rumor, and that becomes legend or urban legend, or ghost town legend or whatever. That's how some of that stuff starts.

Do these stories make you think, in 2020, there are times where the pendulum swings too far in the cynical direction where we don't even entertain the possibility of these odd tales?

Englund: Yeah, we could be a Doubting Thomas. We keep finding new missing links, and we keep finding new aboriginal source material to our own species. Who is to say, in 1840, there wasn't a big lizard in the Southwest that could glide a little bit from rock to rock that looked a little bit like a dinosaur. A monitor lizard with a lot of fat under its arms catching some Santa Ana wind and jumping from rock to rock like a flying squirrel?

Finally, I’d love to hear you tell me a story. Were there any stories or urban legends from your youth in Glendale, California, that personally captures that True Terror type of story?

Englund: Most of mine were traditional. I was born on the edge of Glendale in the Hollywood Hills there in Los Feliz …

Oh yeah, you had Black Dahlia, you had the Los Feliz Murder House …

Englund: I actually lived across the street from that Frank Lloyd Wright Jr. House for a while, the Black Dahlia house. I lived in an apartment directly across the street from it for many years. But I was raised in the valley, so I was a valley boy. So, I heard the urban legends of the hook man on Lover's Lane, which is sort of like every town has an Elm Street. But I have two that were specific to me.

There was a famous, famous flood in the 1930s in Los Angeles, and it was a terrible, terrible hundred-year flood. My mother was in college and she was in a sorority in the foothills of Montrose, up there, Pasadena, Glendale, Montrose there.

People were flopped all over, the ones who couldn't get home were stuck there, and they were all asleep, and it was late at night. My mom was doing the dishes, and putting them in the dish rack and there was a knock on the door, and she went to the door. It was one of the sorority sisters, and she came in all wet and she took off her jacket, and my mother helped her dry her hair. The flood had subsided somewhat, and she got in and they had a cup of coffee. They smoked another couple of cigarettes, and the girl was going to go back. She thought she could get back to where she was staying. She left, and the rain had stopped, and it was calming down. My mother listened to the radio a little more, and went to bed. The next morning there was a loud banging at the door, and it was the police. They wanted to know about this young lady. They knew she was part of the sorority, and they wanted to know if they had a contact number for her parents — because they'd found her body almost 40 hours earlier.

That’s a good one. So, that’s your mother’s ghost story. What’s the other one?

Englund: Here's my father's story. My dad was an executive at Lockheed. He worked on the development of the U2 spy plane, and was involved with the “skunk works” at Lockheed. And I didn't know what he did. I just knew my dad was an engineer, and successful. So, in the 1950s when I was a little boy, we had neighbors across the street my parents were very close to. She was a script doctor for MGM, and he had been a marine — a colonel in the Marine Air Corps — and was now involved in private helicopter business.

When I was a child, he banged on the door, at two, 2:30 in the morning — which in the fifties was kind of outrageous. My father got up, and put a bathrobe on. They talked all night, and had a drink and smoked cigarettes in the kitchen. Close to dawn I think our neighbor went home, and my dad went directly to work. And I heard my mother and father talking about a week later and what had happened was this Marine colonel, this pragmatic, conservative friend of my liberal parents had come to my father in the middle of the night to tell him what he had seen flying back from Catalina in an amphibious PBY executive plane. And he had seen a UFO; he'd had a UFO experience.

It got so close, or they were so close to it, that he actually saw the infrastructure and what looked like seams, and welding, and some kind of riveting that he'd never seen before that almost looked like metal pressed together and creased. He'd seen actual lighting on this thing, and it had moved in perpendiculars, and then just disappeared.

It took my father all night to convince our neighbor not to report it.

I think I know the answer, but why do you think your father didn’t want your neighbor to report it?

Englund: Because, as an officer, as a Marine Corps officer, a high-ranking officer, he had a great pension, and he just had a new baby. My father didn't want him to report it because my father thought that, because they were so strict and so by-the-book, it would hurt his pension, and he didn't want it to hurt our neighbor's pension — even though he believed Bill.

Because of your father’s job in the skunk works, he must have had other stories. Did he share anything else?

Englund: I never got my father to open up about stuff like that. And I never even knew that he was working at the skunk works of Lockheed until years after he retired. My dad would be two or three martinis down in a jazz bar listening to The Tonight Show band, playing after a gig with Johnny Carson, because he loved that band. But that's it, he was still tight lipped. But who knows what our fathers knew? These were the two most strict, by-the-book fathers I knew growing up: my neighbor and my dad. For him to have experienced that, and to have shared that with my pragmatic, no-nonsense dad, it just makes you wonder. It came to me not from UFO fanatics. It came to me through those two guys.

These are sober accounts that come from sober people. Those are the convincing ones to me; the ones that I love to hear.

Englund: That's what I love about True Terror. Even if these were tabloid journalism, they were reported by people who gave it enough credibility back then that they thought we should know about it [such as] Teddy Roosevelt having been source material for a Sasquatch sighting.